What’s happening in Vienna: Gothic Modern

At the Albertina Museum in Vienna, Gothic Modern is currently on view, an exhibition that outlines the key connections between two apparently distant worlds: modern art and Gothic. Among the names on display are leading figures of Symbolism and Expressionism, including Edvard Munch, the author of The Scream.

Before diving into the exhibition itself, however, I feel the need to share a few reflections on its concept.

I believe that, as visitors, we are accustomed to considering national museum exhibitions as adhering to the "secular notions" learned in school; we think of Rembrandt and Caravaggio as Baroque painters, Monet as one of the masters of Impressionism, and Munch as an Expressionist. It is not uncommon to find permanent exhibitions in major national museums that display works according to the 'secular notions' learned in school (at the Albertina, for instance, the well-known show From Monet and the Impressionists to Picasso), and there’s pleasure in that: seeing the works we once studied in books, and finding confirmation of what we learned. It is therefore natural to assume the opposite too: 'if it’s in a museum, it must be the same in the books.'

Following this logic, and considering the possibility of new studies, I found myself imagining Gothic Modern as a newly established art movement, already included in art history curricula. But then, should I think of Munch as Expressionist, or Gothic, or both? Once home, I was contradicted by Google:

Playing with Italian translations (as I was interested in my side of the internet, of course), under “neogotico” I mostly found references to Neo-Gothic architecture, with just a few side notes about other fields. Searching “nuovo gotico” gave me even less: just one interesting result, the website of the painter Piero Colombani, but not much else. Typing “gotico moderno” even brought up results for goth clothing.

So what does that mean? That “Gothic Modern” isn’t a proper art movement? Maybe not yet.

To help me understand the situation, I turned to the introductory article from the Finnish art museum Ateneum, the exhibition's place of origin: It's about new interpretations, which do not seek to replace established artistic movements, but rather to propose a new perspective.

Now I feel lighter.

The start of the exhibition

At the dawn of the twentieth century, the Gothic became modern art’s response to its search for new forms of expression and a crucial source of inspiration for the avant-gardes, even as they distanced themselves from traditional academic models.

With the crisis of Romanticism and the Romantic movements which had previously drawn from the past to construct (with political intentions) narratives of national affirmation,, modern art focused solely on the aesthetic quality of the Gothic period, rediscovering a vivid visual language and all the potential of craft techniques (wood carving, tapestry weaving, glass coloring, and engraving) to address existential themes such as life and death, love, suffering, and grief.

The goal of modern artists to create something new without being constrained by the assumptions of traditional art led many artists to search for aesthetics distant both in time and space. Museums and churches became points of contact with late medieval works that were later reproduced in art magazines, sparking new forms of artistic pilgrimage to France and the cities of Northern Europe that had been united under the flourishing Hanseatic League between the 12th and 17th centuries.

In England, the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood, rejecting Victorian and academic models, looked to Shakespeare, Dante, Botticelli, and Giotto for inspiration — though still within a late-Romantic sensibility. Two decades later, some of them would found the Arts and Crafts movement, opposing industrial mass production with a return to traditional craftsmanship.

Other artists of the time, however, found their inspiration in the intense expressiveness of artists like Albrecht Dürer or Matthias Grünewald (virtually unknown until then, but soon revered as a pilgrimage destination).

In the great cities of the 19th century, rapid industrialization deeply shook society, leading to a period of profound uncertainty that caused many artists to flee toward the simpler, more natural lifestyle of the countryside. In these new rural colonies, the artists, encouraged by interactions with the local inhabitants, started representing the simplicity and authenticity of the poor classes, the harsh living conditions, and the difficulties of physical labor (a novelty compared to the derisive images reflecting the bourgeois mentality). The German artist Käthe Kollwitz, for instance, drew inspiration from the 16th century, choosing the German Peasants' War of 1525 as a tool for criticizing the exploitation, poverty, and precarious living conditions of her own time.

Away from the cities, nature becomes a metaphor for existential fears and human aspirations. Artists found themselves representing the dark forces of nature (and their own human ones) within a dimension of fascination and wonder, but also one that was menacing and sinister, populated by unknown presences and spirits. The genre is not new, but during this period it gained additional dimensions. In Norway, for example, Theodor Kittelsen remained fascinated by the legends of his native land and personified mythical figures in his illustrations. His work still connects with Romanticism in its search for cultural independence and the rediscovery of popular traditions, but it contrasts the charm of the mystical realm with the industrialized world.

Max Klinger, Isle of the Dead (1890), engraving based on Arnold Böcklin, who created the motif, very popular for its melancholic representation.

Death is another major theme that is re-elaborated by modern artists. In medieval art, death was viewed as a necessary limit to life, a moral function, and a reminder of the need for humility and Christian repentance. One of the typical motifs of the Middle Ages is the Danse macabre: the seductive and friendly invitation of Death, involving all social classes, to join the dance. (below, Hans Holbein the Younger, Dance of Death [1523-1526], woodcuts)

At the dawn of the 20th century, discoveries in the medical and scientific fields made the world a place with fewer mortal dangers, but not for all segments of the population. Proletarians and farmers rarely enjoyed the promises of modernity. Wars, epidemics, and hard times meant that their lives were still very similar to those of the Middle Ages but their conception of death was no longer one of solace: once seen as an inevitable companion, it now carried psychological and symbolic meanings and, above all, it left aside the religious and moral aspect in favor of an existential crisis, a search for meaning. Thoughts of one's own mortality and the omnipresence of death transformed into states of anxiety, into emotions difficult to counteract, made even more intense by the context of the First World War.

Perhaps also in response to all this, the medieval representation of death takes on notes of eroticism.

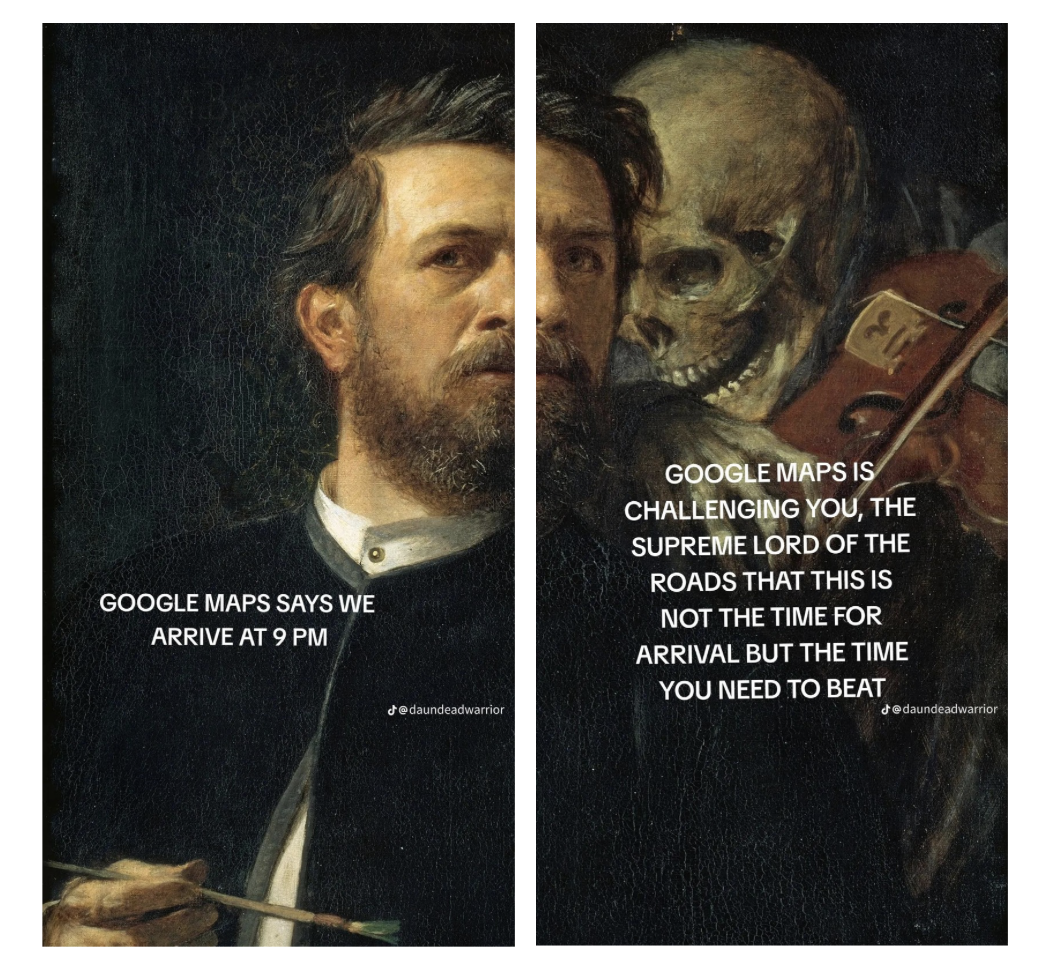

A little background story: At this point in the exhibition lies the painting that had first convinced me to visit. It was the subject of a meme last year, which perhaps some may still remember...

One version of the meme

The artist, Arnold Böcklin, known for The Isle of the Dead, revisits here the theme of the Danse Macabre, representing himself not as a memento mori for him but as a message to the observer. He, in fact, is already immortal in his work and shows no fear of Death, who instead appears to us as his friend, accomplice, and advisor. I won't deny that, in my head, while looking at the painting, I made them both speak just like the meme I've grown to appreciate over time. Right beside it, behind thick glass, stands Van Gogh’s Skull with Burning Cigarette — the official image of the exhibition.

It might seem contradictory to think that in these modern times, marked by profound social changes, artists like the aforementioned Käthe Kollwitz and Edvard Munch continued to show interest in sacred and religious themes. However, the language of these themes adapts to reflect the deep emotions of the new world: fear, uncertainty, and powerlessness. Sacred archetypes are reworked, dismantled by the academic system, and repurposed as critical metaphors for society, used to address fundamental themes such as motherhood and femininity, the relationship between man and woman, and the human relation with sexuality and desire.

The medieval-era demonization of women is reflected into a visual depictions of witches, images certainly intended to frighten the viewer but also to arouse them, as we see here from the exhibited works by Hans Baldung Grien, which, though seemingly intended to portray immorality, nevertheless reveal a clear delight in eroticism. Contorted, sometimes unusual gestures and poses are present not only in these erotic depictions but also in those of martyrs and saints, becoming striking points of reference for artists such as Egon Schiele.

Personal note: the only work by Lovis Corinth presented at the exhibition is indeed connected to the theme of the sacred, yet in my opinion it fails to adequately represent the painter’s body of work, which I discovered by chance and briefly present below (and which, in fact, would have fit perfectly with the themes explored, even with that of the witches’ sensuality).

As already mentioned before delving into the exhibition's themes, the connection between Gothic and modern architecture is evident and certainly more well-known than the other topics just covered. Perhaps this is why the room related to this subject is much smaller than the others. I also believe that, historically, it has already been widely discussed and analyzed, so I don’t feel the need to elaborate further on this. Instead, it’s time to draw some conclusions.

With contemporary art often inclined to focus solely on its aesthetic, performative, and ephemeral aspects, one might think that artistic reflection on such themes has run its course. However, realizing that the voices of the modern artists still resonate today, that the needs and emotions they express address universal and recurring themes in human experience, and that their criticism of society and inequality denounces not only their times but also ours, perhaps shows us that, despite everything, we have not fully emerged from the Middle Ages yet. And that, especially on the cusp of new and disruptive changes, amid anxieties and fears that have never quite healed, this exhibition is truly worth seeing.